The history of research on the ecology of treefall gaps goes as far back as the 1930s. Since then, a rich volume of literature has been generated on Gap Phase Dynamics. These include testing highly influential predictions and hypotheses that aim to explain the complex trade-off between colonization and competition. But, how did the idea of Gap Phase Dynamics germinate and take root? What are the key tenets of this widespread natural event? How did the thinking of the 19th century naturalists evolve to include treefall gaps as an integral part of the natural forest regeneration cycle? As observations from the tropical forests accumulated, early notions centered on temperate and boreal zone forests began to change. Albeit slow, a paradigm shift took place in the early 20th century. The view of successionally stable climax tree communities began to change in favor of dynamic mosaic forest landscapes. These landscapes were a product of regenerating forest patches after disturbance. Now equipped with state of the art technologies and methods such as airborne lidar and drone photogrammetry, the canopy gap research has come a long way. As we increasingly face the grim consequences of human induced climate change, a global scale understanding of canopy gap dynamics is critical in estimating land-based carbon stocks. Close to 40 percent of the global terrestrial biomass reside in tropical forests.

Part 1 Germination of the idea:

A historical perspective

Our ideas on forest gap regeneration took generations of scientists to shape and transform into a testable set of hypotheses. Naturalists of the 18th and 19th century took on a grand challenge of understanding species distributions on a global level. It was indeed a grand challenge, since in those times, even the most fundamental biological features of plants such as photosynthesis were not entirely understood. For instance, the relationship between light and oxygenic photosynthesis in plants was established by the Dutch physiologist Jan Ingenhousz in 1779. Legendary expeditions like those of James Cook, Alexander von Humboldt, Henry Walter Bates, Charles Darwin, and Alfred Wallace aimed to catalog taxonomical riches especially pronounced in the tropical regions.

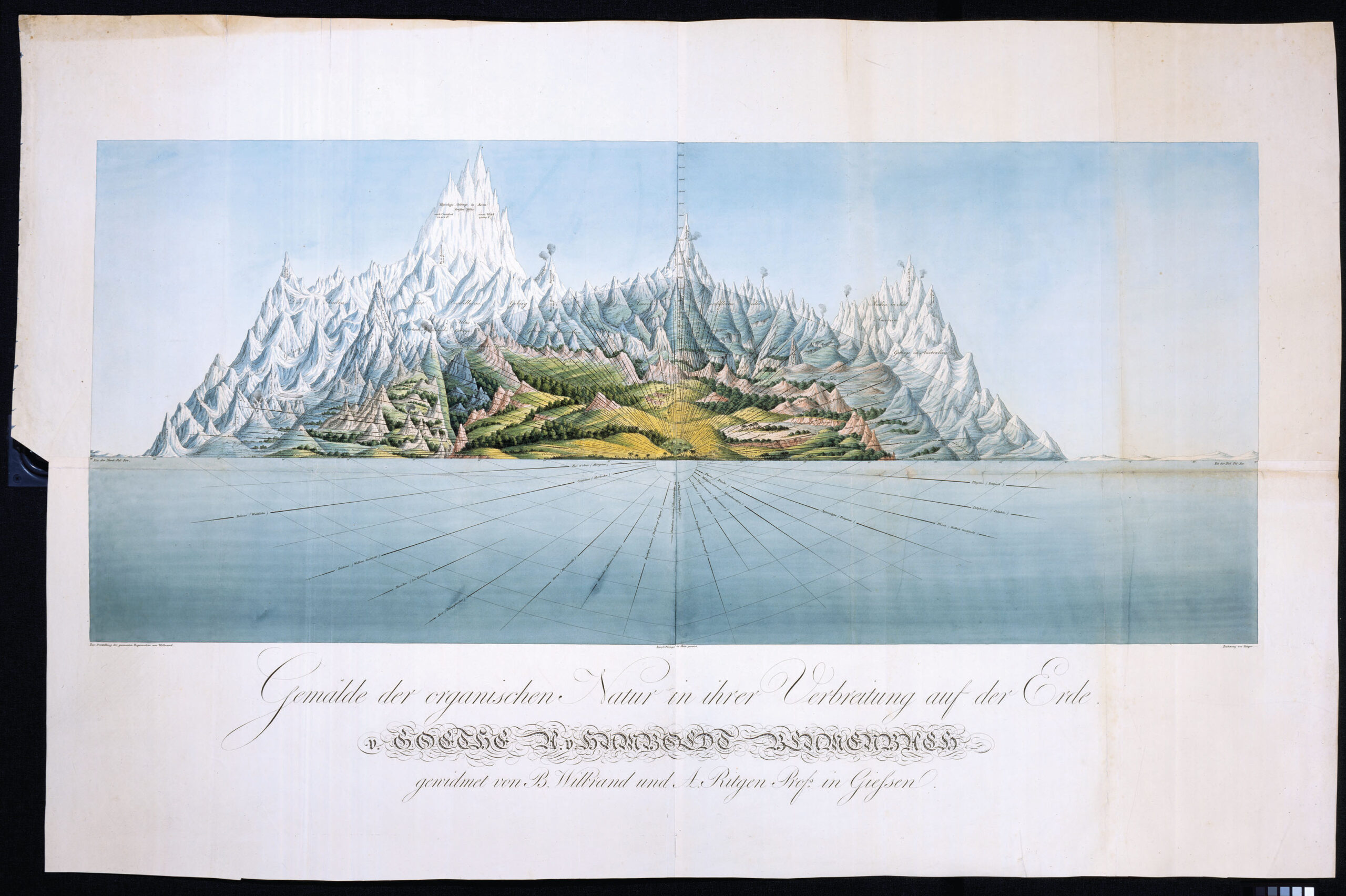

Worldwide distribution of Organic Nature (Gemalde der organischen Natur in ihrer Verbreitung auf der Erde). Hand-colored lithograph by Joseph Paringer based on original work by Ferdinand August von Ritgen and Johann Bernhard Wilbrand. Print C.G. Muller, 1821. In homage to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Alexander von Humboldt, this artwork aims to consolidate global knowledge of plant and animal species’ locations, altitudes, and habitats into a unified visual representation. Humboldt pioneered a method to synthesize biogeographical data, but it was Darwin and Wallace who ultimately provided the unifying theory to explain the interconnectedness of all life.

Ecologists of the early 20th century had a strong notion of stable climax tree communities based on temperate and boreal forests. This outdated view of stability was entirely focused on competitive interactions and largely ignored the role of disturbance on biological communities. Today, the “balance of nature” concept still persists as a relic of this old-fashioned idea. As such, the first quarter of the 20th century was preoccupied with questions on the nature of communities. In 1916, Frederic Edward Clements argued that communities were super-organisms formed through self-organization of species with a co-evolutionary history. In 1918, Henry Allan Gleason provided a counter argument with the Individualistic Continuum concept, describing communities as random sets of populations with minimal functional integration. However, things began to change when studies from species rich tropical forests started to synthesize the taxonomic diversity through the perspective of ecology and evolutionary biology. In 1938, the French botanist André Aubréville linked variability in the dominant forest species to regenerative success and failure. Aubréville’s view was further promoted by others such as Alexander Stuart Watt and Paul Westmacott Richards under the terms “mosaic” or “cyclical” pattern of regeneration. Ecologists began to favor the idea of a forest growth cycle consisting of a dynamic equilibrium among gap, building, and mature phases instead of a stable equilibrium leading to a climax community. In order to test this highly hypothetical and descriptive concept of forest growth cycle, ecologists set out a rigorous research effort under an umbrella term “gap phase dynamics”.

In 1978, Joseph H. Connell proposed one of the most influential hypotheses in gap phase dynamics research known as the Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis. The Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis predicts that the local species diversity is maximized when ecological disturbance occurs at an intermediate frequency and intensity. Treefall gaps fit into this prediction quite nicely since disturbance caused by a few trees is modest in scale compared to those of fire, landslides, avalanches or hurricanes.

Part 2 Overview of Gap Phase Dynamics

Treefall gap dynamics refers to changes in the composition of plant species in a forest over time driven by disturbance. Disturbances arising from physical conditions, herbivory or disease break the uniformity of the forest structure and open gaps for colonization and growth. Here is a medium size, approximately 40 meters long, 15 meters wide windthrow gap formed by multiple trees in Barro Colorado Island, Panama. This is home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, and is one of the most intensely studied ecological sites concerning treefall gap dynamics. In treefall gaps, species adapted to colonize fast arrive early and begin occupying a niche. Under a moderate level of disturbance, the forest becomes a patchwork made up of phases corresponding to different intervals of regeneration. Disturbance leads to a gradient of environments serving as critical life rafts for many species. Some seeds and seedlings may depend on the temporary habitat diversity created by treefalls for successful establishment. The transient habitat heterogeneity generated by treefalls might be key for establishment of some seeds and become seedlings.

The most common disturbance is windthrow combined with overloading by rain. But there are numerous other causes for tree mortality including disease and lightning strikes. In fact, one of the main causes (~50%) of large tree mortality in tropical forests is lightning strikes which can lead to formation of large gaps. The video below captures the death and damage caused by a single lightning strike in Panama.

In the documentary, two adjacent canopy gaps formed by windthrow and disease is shown in a Dipterocarp dominated rainforest within Bukit Timah Nature Reserve in Singapore. Trees may also die standing due to a combination of below-ground and above-ground competition. Canopy gaps allow bursts of photosynthetically active radiation to reach saplings and established seedlings, whose growth may have been suppressed for decades.

While light is a primary driver of treefall gap growth, temperature, moisture, and soil properties also play crucial roles. Increased light in a gap alters soil temperature, moisture, and nutrient cycling through changes in vegetation and root activity. Pit-and-mound formations, resulting from overturned root plates and litter disturbance, represent some of the changes in soil surface properties.

Forest layers, canopy heterogeneity, treefall gaps

The definition of “plant canopy” refers to all parts of the above-ground vegetation. However, biologists generally refer to the cluster of tree crowns including leaves, fine branches and epiphytes. Ecologists frequently use terms such as canopy, subcanopy and understory to describe plants forming vertical layers of a forest. However, this is a rather arbitrary nomenclature with no clear distinction especially for what constitutes a subcanopy tree. In the tropics, fascinatingly tall emergent trees lead to a highly heterogeneous canopy. Some temperate forest trees such as the tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) can attain emergent status.

Old-growth forests have an uneven height structure due to different aged trees, broken branches, fascinatingly tall emergent trees and treefalls. On the other hand, younger second-growth forests regenerating after disturbance have a more homogeneous canopy and treefalls are less frequent.

When trees fall, they often smash their neighbors as well. In an instant, a large gap may form by removal of healthy trees. Treefalls may become especially drastic when an emergent giant tree topples over creating a “domino effect”. The toppling of a large, emergent tree can induce a domino effect, leading to significant tree mortality.

Part 3 The role of light in Treefall Gaps

Intense competition for light has been a selective pressure on land plants throughout their evolutionary history. Early woody forests began to evolve during the Devonian. The evolution of genes coding for key enzymes involved in lignin production was a key event in the evolution of efficient vascular systems carrying water and nutrients. And thus, lignin became a major polymer in the wood providing structural support and paved the way to the formation of vertically layered forest canopies. Under a closed canopy, less than 2 percent of daylight reaches the forest floor even on cloudless days. Gaps in the canopy provide photosynthetic boost to the overshadowed plants in all forest types including boreal, temperate and tropical.

Plants in the understory may have to wait a long time until a canopy gap forms. Until then, as a shade-avoidance response, some temperate tree seedlings have adapted to leaf out earlier in the spring. Early expansion of leaves extends photosynthesis by more than a week at the very beginning of the growing season. However, false spring events make this a rather risky strategy. Human induced global warming and resulting climate change have increased the likelihood of false spring events. The red maple (Acer rubrum) seedling here is at least four years old. The data shows that each year, global warming is pushing the arrival of spring to earlier dates. This is particularly worrying for species reliant on day length for leaf emergence, as they may be outcompeted by those less sensitive to photoperiod.

Canopy gaps allow direct penetration of sunflecks to the understory. Treefall gaps sharply increase light availability and trigger regenerative growth. Until a canopy gap opens, understory saplings remain acclimated to low light, utilizing far-red light spectrum. At the same time, they are poised to harness sunflecks. During lowlight acclimated state, the non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) in the Photosystem II (PSII) antenna system fine-tuning the photosynthetic apparatus. Here, a sapling growing under a closed canopy in Panama experiences a short duration sunfleck. Under closed canopy, sunflecks may constitute up to 80 percent of the total photosynthesis.

Shade tolerant plants have higher light interception efficiency and lower light compensation points. However, sudden exposure of leaves to high intensity light can be detrimental. The powerful photosynthetic reaction center that splits water to release oxygen can sustain damage with the sudden flux of photons. During a sunfleck, most plants switch their light harvesting complexes into an energy dissipating, photoprotective mode. As soon as the sunfleck is over, shade-tolerant plants can rapidly transition back to the lowlight acclimated state. Slow reversibility into lowlight acclimated photosynthesis leads to losses in carbon fixation.

Shown here is a profile of daily fluctuation of light within the canopy. A section of the light profile is expanded to visualize the photosynthetic losses during light fluctuations. Dashed lines represent the response lags. The area between the solid and dashed lines represents the reduction in photosynthesis.

Measurements of simulated sunfleck responses in the shade tolerant Chinese ginseng have demonstrated the immediate restoration of low-light acclimation. The sunfleck responses are generated by the components of the electron transport system in the thylakoid membrane such as the photosystem I and the photosystem II (PSII). These responses include Maximum Quantum Yield as well as Effective Quantum Efficiency pertaining to photosystem 2, Cyclic Electron Flow around photosystem I, and Non-photochemical Quenching.

One curious adaptation discovered in the poplar tree is a triple-chimeric gene called “Booster” conferring fast light acclimation. The Booster is a mix of a segment of a gene encoded in the chloroplast [ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (RuBisCO)], and two gene fragments from a bacterium and an ant. The ant farms a fungus infecting the poplar tree. The Booster appears to be a unique gene that has evolved once in the cottonwood lineage, providing a fantastically fast acclimation to fluctuating light. As the Booster gene illustrates, species can evolve diverse molecular mechanisms to cope with light stress. Therefore, the shade-avoidance and tolerance adaptations highlighted here, are just a few examples among many that have evolved against light limitation.

Part 4 Root plate dynamics

The upturned root plates of fallen trees disrupt the soil environment, setting the stage for new competitive interactions. A characteristic of old-growth forests is the heterogeneity in the microtopography of the forest floor due to root plate dynamics. Upturned root plates form a significant fraction of bioturbation affecting leaf litter and soil mineral mixing. Ecologists refer to this type of forest floor surface texture as pit-and-mound topography.

As a tree is uprooted, it pulls up soil and roots, leaving behind a pit in the forest floor. The soil matrix pulled out of the ground piles into a mound converting the disturbed area into a nutrient hot spot with higher rates of decomposition and mineralization. The domino effect in the canopy can mirror down to the root plates, and may orchestrate larger soil disturbances. Overturning root plates redistribute the thickly accumulated leaf litter. Litter gaps could be essential for germination of certain seeds. For instance, tropical tree seeds cannot remain dormant for too long after dispersal. This is due to a heavy threat from predation and disease. Therefore, tropical forests don’t have a seed bank in the soil. Litter gaps formed by upturned root plates could be especially necessary for the germination of the newly produced seeds.

The sequence of root plate dynamics has been well characterized on a temporal scale spanning decades. Throughout the sequence, soil horizons are reworked due to weathering processes such as particle fall, sheet wash, and rain splash. The remains of trees uprooted by windstorms are frequently found in European archaeological sites, which can be easily confused with the foundations of Neolithic dwellings. Windthrow traces are quite common in European archeological sites, and can complicate excavations by false recognition as neolithic chalets. To avoid wrong interpretations, archeologists have studied the micro-stratigraphy of pit-and-mound formations in great detail.

The disturbance of sedimentary deposits by living organisms is called bioturbation. The impact of root plates on bioturbation rates becomes particularly noticeable on sloped terrain. The downslope movement of uprooted trees results in higher soil mixing.

The influence of root plates on soil bioturbation is more pronounced on slopes, as trees falling downhill can disrupt the soil profile. The upheaved root plates may break up bedrock, transport soil downslope, increase the heterogeneity of soil respiration rates, and stir soil horizons. Pits formed by root plates collect rainwater and increase seepage to the underground. These pits also provide microhabitats to moisture-loving organisms. Seedlings, saplings, and neighboring trees that successfully adapt to pit-and-mound topography will have a greater chance of survival.

Part 5 Photogrammetry of treefalls.

Photogrammetry is a method of reconstructing three dimensional models from overlapping sequences of images. In 2014, Hurricane Gonzalo generated powerful tornadoes and uprooted many trees in Athens, Georgia of the United States as can be seen in a panorama of a treefall gap formed by multiple trees in Oconee Forest Park, Athens, Georgia, USA. Here, you see an animation based on a photogrammetric model of the same treefall gap. This three dimensional point cloud model was generated from over five thousand overlapping photographs using the application RealityCapture. The original camera positions are visualized by little white triangles surrounding the root plates. The flight path, and keyframes guiding the virtual camera are shown in blue.

Photogrammetry provides a versatile tool for accurate quantification of many parameters and indices used in studies of forest gaps. Photogrammetric monitoring can be useful for understanding the dynamics of material cycling in forest ecosystems. For instance, volumetric measurements of pits and mounds can quantify bioturbation rates. Similarly, detailed reconstructions of gaps allow estimation of light levels and growth based on the day of the year and latitude.

The spatial data can be very informative when collected in a time series, allowing comparison of growth patterns. The power of time-series photogrammetry is evident from a study that used drone imagery collected in monthly intervals in Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Here, a canopy gap is photogrammetrically reconstructed based on sets of images taken a month apart. The disturbed area is delineated by a blue line. Photogrammetric elevation models can quantify treefall gaps with great accuracy. The black area in the grayscale panel shows a sharp drop in the canopy.

NASA Goddard’s G-LiHT Airborne Monitoring System

G-LiHT is an airborne imaging system operated by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Using LiDAR and hyperspectral-thermal imager, it collects multi-layered data to map terrestrial ecosystems. The LiDAR instrument sends out rapidly pulsating laser beams at a rate of 600,000 pulses per second that bounce off of leaves and branches. Returning laser signal enables rendition of canopy height as a point cloud. NASA researchers compared detailed 3D point cloud renditions of forest canopies in the Brazilian Amazon captured during aerial surveys in 2013, 2014, and 2016. Here, data from 30-mile swaths near Santarém, Brazil, showed trees present in 2013 were likely logged by 2016.

Puerto Rico exemplifies a tropical forest adapted to extreme hurricane disturbance. Forest types of the island are well-defined along its altitudinal gradients. In another series of G-LiHT flight campaigns to Puerto Rico, Hurricane Maria’s devastating impact on El Yunque National Forest can be seen in this split-screen visualization. The dense, lush forest canopy of 2017 captured before hurricane Maria is on the left. The thinned canopy of 2018 is on the right. After the hurricane, the forest floor became more exposed.

Frequent hurricane disturbance makes this island a prime location for research focusing on adaptations to rapid forest recovery. To understand the resilience of these forests, we must investigate the adaptations that act as the lynchpin of community assembly. How the gap phase dynamics will play out during post-Hurricane Maria regeneration is a subject worth investigating. The utilization of photogrammetry, LiDAR, and hyperspectral-thermal imaging provides a significant enhancement in our capacity to comprehend the rapid transformations occurring within forest ecosystems.

Treefall Gap Dynamics has been a hot subject for many decades, especially among tropical ecologists, for it carries clues to how diversity is maintained in ultra-species rich forests. By compiling footage from tropical and temperate forests from Panama, Singapore, Turkey, and the United States, this documentary is an attempt to summarize key elements of this ecological phenomenon.

If forest managers can support conditions that favor mosaics of communities that mimic the patchy and cyclical dynamics of unmanaged forests, the conservation value of lands under human pressure can increase.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.